Ten years ago this month, the initial results of a $10 million depression treatment project funded by the Hartford Foundation (with co-funding from the California HealthCare, Hogg, and Robert Johnson Foundations) were published in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Ten years ago this month, the initial results of a $10 million depression treatment project funded by the Hartford Foundation (with co-funding from the California HealthCare, Hogg, and Robert Johnson Foundations) were published in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

In what remains the largest multi-site randomized trial of its kind, the project—called IMPACT—showed that it is possible to double the benefits of the usual treatment of older adults for depression in primary care practices. And it demonstrated what changes are needed in the process of depression care to ensure that more patients get better.

So how much progress has our nation made in providing better mental health care for older adults, a decade later? To find out, we commissioned our second national poll, with help from Strategic Communications and Planning, called “Silver and Blue: The Unfinished Business of Mental Health Care for Older Adults.”

From Nov. 16-26, Lake Research Partners surveyed 1,318 Americans age 65 and older. As we expected, we found that depression and other mental health issues are common among older Americans, with some 20 percent reporting being told by a professional that they had some mental health issue, and 14 percent reporting depression. (Please visit this page for full poll results and more information.)

While we found that some progress has indeed been made over the past decade, especially in the area of reducing the stigma attached to depression and other mental health conditions, we also found stark evidence of how far we still have to go to relieve the suffering of too many older adults and their families.

Among the key findings were:

- Even though clinical experience shows that the first treatment employed to combat depression fails as much as 70 percent of the time, almost half of those currently receiving treatment say their provider did not follow up with them within a few weeks of starting treatment to see how they were doing.

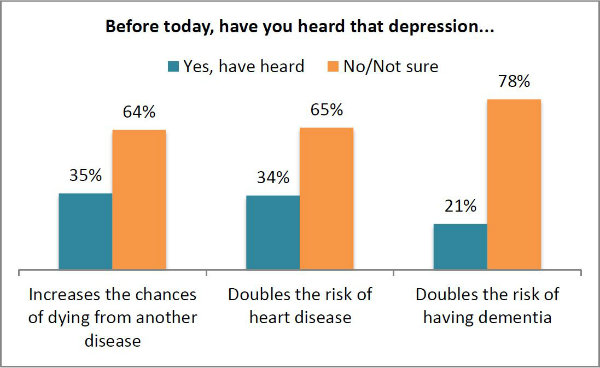

- Among all respondents, very few understood the serious health risks posed by depression. Only one in five (21 percent) knew that depression doubles the risk of dementia; just 34 percent were aware that depression doubles the risk of heart disease; and only 35 percent knew that depression increases the chances of dying from another disease.

When we asked about the aspects of the IMPACT care model that evidence shows are important to obtain improved outcomes, we found that elements of quality of care are still lacking. People are not being adequately informed and engaged in their care nor are they receiving adequate follow-up and adjustment to their treatments.

When we asked about the aspects of the IMPACT care model that evidence shows are important to obtain improved outcomes, we found that elements of quality of care are still lacking. People are not being adequately informed and engaged in their care nor are they receiving adequate follow-up and adjustment to their treatments.

Specifically, respondents said their providers:

- Had not discussed possible side effects (38 percent);

- Had not discussed different treatment options (33 percent);

- Had not worked with them to decide which treatment would be best (22 percent);

- Had not explained how long treatment would take (40 percent);

- Had not discussed what to do if they felt worse (34 percent); or

- Had not followed up within a few weeks to see how they were doing with treatment (46 percent)

As an indication of just how far we still have to go, 15 percent said their provider had not done any of those things. And 49 percent said their doctor had done fewer than half of the actions.

We also asked respondents to describe how it feels to be depressed or anxious, and in their own voices, you can hear the terrible toll that depression takes. “It was as if I were falling into a deep dark well and I could not climb out of it. I had no energy. I was lethargic and moody. My family suffered too because there was nothing they could do to help.” Others described it as “dark, gray, lonely, slow;” “like you would prefer to be dead;” and “like a rapidly vibrating piece of tin stuck in a concrete slab.”

The United States spends more than $10 billion a year on antidepressant prescription medications and 93 percent of those surveyed who are currently receiving treatment are on medication.

And 63 percent of those currently receiving treatment reported that they had felt nervous, anxious or on edge for several days or more in the past two weeks, with almost half (47 percent) saying they felt down, depressed or hopeless for several days in that same period.

We can, and must, do better.

For those who are interested, you may also want to read our 2011 annual report on Mental Health and Aging, view the patient videos we commissioned, and learn about our continuing work to spread effective depression care through our Social Innovation Fund grant.